The production process of Talavera has remained almost unchanged since colonial times. The process employs two different kinds of clay: white and black, combined in equal parts.

To prepare the clay, the first step is cleaning it, by putting it through a sieve, mixing it and placing in it in sedimentation tubs, until excess water is dried out. This “maturation” process increases the quality and plasticity of the clay.

Next, the clay is “stepped on”, that is, it is kneaded by having someone walk over it to obtain a uniform consistency and humidity. Afterwards, blocks are formed and the clay is stored.

Next, the clay is “stepped on”, that is, it is kneaded by having someone walk over it to obtain a uniform consistency and humidity. Afterwards, blocks are formed and the clay is stored.

Production can be done in one of two ways: by using the potter’s wheel, or through the use of molds, over which clay plates are placed. Once the pieces are completed, they are stored in unventilated spaces for a long period of time, so they can dry slowly and uniformly.

Afterwards, the pieces go into the kiln for the first time, for a period of about 10 hours.

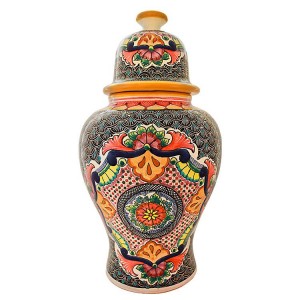

Then, an enamel made of tin and lead is applied through an immersion process. This layer is the basis for the decoration.

The designs are selected along with the colors, which are prepared with mineral pigments, respecting the traditional colors of the Talavera of Puebla.

Finally, they go into the kiln for a second time. This is where colors obtain their characteristic shine and volume.