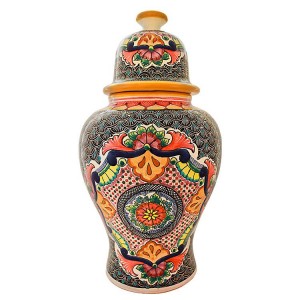

Of the tin-glazed earthenware made in colonial Spanish America, the variety known as Talavera Poblana is perhaps the most important. It has certainly enjoyed the longest continuous tradition and is still manufactured today as it was .several centuries ago. It was also the pottery that achieved the widest distribution in America, precisely because it was one of the most important products in the trade established between colonies.

Puebla’s pottery workshops were held in especially high esteem and their production included objects of everyday use, as well as ornamental pieces of particular artistic value. During the eighteenth century some workshops in Puebla even took part in decorating certain buildings in tile which consequently gave the city’s architecture its unmistakably local color.

The origin of earthenware production in Puebla has interested authors for decades. In his book entitled The Majolica of Mexico (1908), Edwin Atlee Barber upheld the popular belief that Talavera was instituted in the recently founded City of Puebla by monks at the Santo Domingo Monastery. It was thought these friars had sent for potters from Talavera de la Reina in Spain to circulate their techniques for producing ceramics. This theory has long been prevalent and is still reiterated, if often spiced with a dash of legend.

The archival research published by Enrique Cervantes affirms that the production of earthenware in Puebla began in the sixteenth century. Cervantes appropriated the hypothesis advanced by Antonio Peirafiel which states that among the first citizens of Puebla were several artisans from Toledo who established the pottery industry in 1531. Completely discarding the myth that the first potters were commissioned by monks at the Santo Domingo Monastery, Cervantes concludes (without citing his sources), that there is enough information to assume that pottery began to be manufactured between 1550 and 1570; and that moreover, between 1580 and 1585, Gaspar de Encinas, a potter from Puebla, had already set up a workshop on the Calle de los Herreros. Closely examining these documents, however, we can only affirm that by 1573 the potter Alberto de Ojeda began working in Puebla and that the following year he and Bartolame de Reina established a business partnership to make earthenware of all varieties, including tiles.” In 1573, another artisan from Puebla by the name of Diego Rodriguez (referring to himself as a master potter), effected a contract in Mexico City with the friar Hernando de Morales to make 1500 tiles and verduguillos (rectangular tile pieces) for the Santo Domingo Monastery. That same year Rodriguez made arrangements for ceramics-painter Domingo de los Angeles to decorate the tiles that had been bought for the monastery. Rodriguez remained in Mexico City until at least 1582 which allows us to assume that he was the first to bring earthenware and tiles to Mexico City, and later to Puebla.

In 1579, “a master potter” by the name of Antonio Xinoves began working in Puebla and by the following year formed a seven-month partnership with JerOnimo Perez to do business, and profit from making earthenware.” That same year he contracted the services of someone named Juan Portuguez to help him with the work.

By 1580 many other potters had begun to settle in Puebla where they not only found the materials needed to produce quality earthenware, but were also furnished with a business center which facilitated the sale of their products to various cities in New Spain.

The production of earthenware became so important that by the late sixteenth century it sparked the interest of ecclesiastical authorities at the Bishopric of Tlaxcala who wanted to impose a tithe on these products. Potters were naturally opposed and eventually won the dispute by arguing that in Spain earthenware was not subject to any tithe.

It is hard to determine exactly how many “white ceramic workshops” could be counted in Puebla during the first half of the seventeenth century. Though quite a number of potters and craftsmen are mentioned in archives, many of them established companies to produce pottery and tiles for varying—often very short lengths of time—which makes it difficult to specify how many workshops there were, and how long each lasted. Nonetheless, documents regarding commercial operations and services (as well as personal letters and those drawn up to contract apprentices) give us a partial idea of their activities.

In the early seventeenth century, some potters must have produced their earthenware with the help of only a few apprentices and craftsmen. By the end of the century, however, this began to change as the number of craftsmen gradually began to increase. These artisans were primarily Indian and in some rare cases, black or mulatto slaves. By the eighteenth century, workshops began evolving into actual factories, including a master potter and artisans and apprentices under the control of an owner who wasn’t always a potter himself—or herself, as was often true when ceramic workshops were run by the widowed wives of potters with the help of craftsmen and servants.

Article excerpt from Artes de Mexico Magazine – June 1992