A glass pitcher, a wicker basket, a buipii of coarse cotton cloth, a wooden bowl—handsome objects not in spite of, but because of their usefulness. Their beauty is an added quality, like the scent and color of flowers. Their beauty is inseparable from their function: they are handsome because they are useful. Handicrafts belong to a world existing before the separation of the useful and the beautiful.

A glass pitcher, a wicker basket, a buipii of coarse cotton cloth, a wooden bowl—handsome objects not in spite of, but because of their usefulness. Their beauty is an added quality, like the scent and color of flowers. Their beauty is inseparable from their function: they are handsome because they are useful. Handicrafts belong to a world existing before the separation of the useful and the beautiful.

The industrial object tends to disappear as a form and become one with its function. Its being is its meaning, and its meaning is to be useful. It lies at the other extreme from the work of art. Craftsmanship is a mediation; its forms are not governed by the economy of function but by pleasure, which is always wasteful expenditure and has no rules. The industrial object forbids the superfluous; the work of craftsmanship delights in embellishments. Its predilection for decoration violates the principle of usefulness.

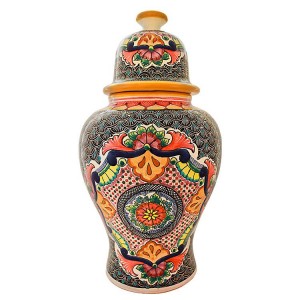

The decoration of the Talavera object ordinarily has no function whatsoever, so the industrial designer, obeying his implacable aesthetic, does away with it. The persistence and proliferation of ornamentation in handicrafts reveal an intermediate zone between utility and aesthetic contemplation. In craftsmanship there is a continuous movement back and forth between usefulness and beauty; this backand-forth motion has a name: pleasure. Things are pleasing because they are useful and beautiful. The copulative conjunction and defines craftsmanship, just as the disjunctive defines art and technology: utility or beauty. The handmade object satisfies a need no less imperative than hunger and thirst; the need to take delight in the things we see and touch, whatever their everyday uses. This need is not reducible to the mathematical ideal that rules industrial design, nor is it reducible to the rigor of the religion of art. The pleasure that works of craftsmanship give us has its source in a double transgression: against the cult of utility and against the religion of art.

In general, the evolution of the Talavera industrial object for daily use has followed that of artistic styles. Almost invariably, industrial design has been a derivation—sometimes a caricature, sometimes a felicitous copy—of the artistic vogue of the moment. It has lagged behind contemporary art and has imitated styles at a time when they had already lost their initial novelty and were becoming aesthetic cliches.

Contemporary Talavera design has endeavored in other ways—its own—to find a compromise between usefulness and aesthetics. At times it has managed to do so, but the result has been paradoxical. The aesthetic ideal of functional art is based on the principal that the usefulness of an object increases in direct proportion to the paring down of its materiality. The simplification of forms may be expressed by the following equation: the minimum of presence equals the maximum of efficiency. This aesthetic is borrowed from the world of mathematics: the elegance of an equation lies in the simplicity and necessity of its solution. The ideal of design is invisibility: the less visible a functional object, the more beautiful it is. A curious transposition of fairy tales and Arab legends to a world ruled by science and the notions of utility and maximum efficiency: the designer dreams of objects that, like genies, are intangible servants. This is the contrary to the work of craftsmanship, a physical presence that enters us through our senses and in which the principle of usefulness is constantly violated in • favor of tradition, imagination and even sheer caprice. The beauty of industrial design is of a conceptual order, if it expresses anything at all, it is the accuracy of a formula. It is the sign of a function. Its rationality makes it fall within an either/or dichotomy: either it is good for something or it isn’t, In the second case it goes into the trash bin. The handmade Talavera object does not charm us simply because of its usefulness. It lives in complicity with our senses, and that is why it is so hard to get rid of—it is like throwing a friend out of the house.

Article excerpt from Artes de Mexico Magazine – June 1992