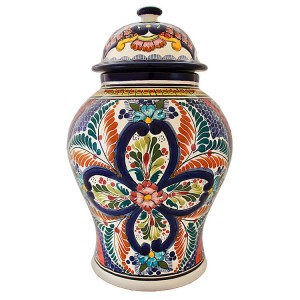

Since its introduction by Spanish settlers in the 16th century, talavera pottery has become synonymous with Puebla. The beautifully hand-crafted ceramics, which take the form of everything from garden tiles to dinnerware, adorn building fronts in the historic center, replace china sets in Mexican households, and travel home with visitors as souvenirs. Talavera is so revered that President Calderón ordered a special bicentennial pattern last year for his Independence Day state dinner; Governor Rafael Moreno Valle buys centerpieces to give as personal gifts; and collectors worldwide seek out new and historical pieces to display as fine art.

Since its introduction by Spanish settlers in the 16th century, talavera pottery has become synonymous with Puebla. The beautifully hand-crafted ceramics, which take the form of everything from garden tiles to dinnerware, adorn building fronts in the historic center, replace china sets in Mexican households, and travel home with visitors as souvenirs. Talavera is so revered that President Calderón ordered a special bicentennial pattern last year for his Independence Day state dinner; Governor Rafael Moreno Valle buys centerpieces to give as personal gifts; and collectors worldwide seek out new and historical pieces to display as fine art.

The local tradition of making talavera started shortly after the city of Puebla was founded in 1531. “The Spanish feverishly began building churches, monasteries, and convents,” notes MexOnline.com. “To decorate these buildings, craftsman from Talavera de la Reina … were commissioned to come to the New World to produce fine tiles as well as other ceramic ware. In addition, these same craftsman were to teach the indigenous artisans their technique of Majolica pottery, in order to increase production levels.”

Nearly 500 years later, artisans continue to produce talavera in Puebla. In fact, the capital city is home to the longest continuously operating factory in Mexico and perhaps the world: Uriarte Talavera. Uriarte is one of the oldest businesses in the country, ranking in the top 10 behind José Cuervo’s tequila distillery in Jalisco and several other well-known enterprises.