Works of art good enough to eat off – that’s the essence of Talavera pottery.

Works of art good enough to eat off – that’s the essence of Talavera pottery.

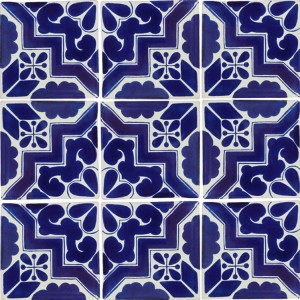

The Mexican pottery, which has been around for 400 years and is primarily made in Puebla City, is an artistic and practical achievement. Vases, cups, plates, serving bowls, and tiles, called azulejos, are some of the items I saw being made in Uriate Talavera factory where the highly regarded, expensive pottery is hand made. The factory, which was established in 1824, is one of Puebla city’s most renowned because it is one of the few authentic Talavera workshops left today. Talavera is one of Mexico’s most unique items, making it a worthwhile gift to bring home.

Puebla City is located sixty miles southeast of Mexico City, making it a convenient hop, skip, and a jump away – and a convenient escape – from Mexico City, which is the world’s largest. Puebla City, which is also the capital of the same name state, is the country’s fourth largest urban center. Approximately two million people live there. The residents, who call themselves poblanos, live in the most European of all of Mexico’s colonial cities. The Spanish established and planned the 16th century city from the ground up, rather than building it within an existing indigenous community. They did this because the location was on the main route between Mexico City and Veracruz, which was at that time the most important port in the country. Puebla City is situated at a height of 7,000 feet above sea level and is blessed with a temperate, year round climate.

While the Spanish may have first introduced the highly decorative art from their home country when they settled in the heart of Mexico, diverse artistic styles, including Moorish and Oriental cultural nuances transformed the colonizer’s craft to what it is today. The Moorish influence of cobalt blue patterns on white appeared on Mexican pottery around the late 15th century, while the Oriental styles of animals and floral designs were first seen in the mid-16th century. To be authentic, Talavera pottery (named after a town in Spain) must be hand-painted in intricate designs using natural dyes derived from minerals. The colors used include blue, black, yellow, green and reddish pink. During a ninety-minute tour of the factory, we learned just how long it takes to make these detailed works of art. And while the pottery is expensive to purchase, even at the point of production, our tour helped us understand why. The factory usually offers free tours that are shorter, but our group of writers was interested in learning minute details about how the pottery is made.

First, black or white clay is soaked for several days in water to soften it, said Angela Garcia, the cheerful tour guide who patiently answered all our questions. Both colors give the same end pink result, she said, but only clays from four areas, Puebla, Cholula, Tecalli and Amococ, are used in making Talavera pottery. A sieve is used to strain the clay, which breaks it into fine, uniform particles that will give the earthenware a smoother finish. The clay is then left in vats for several days to separate out the water.

Next, a potter molds the clay, sometimes by hand, and at other times with a potter’s wheel, after which he or she rubs it with a damp sponge to create a fine finish. The molded clay is left in the sun to dry for up to five days, depending on its size. Once the pottery is thoroughly dry, it is baked for about eight hours at 2000 degrees Fahrenheit in a handmade brick oven. We observed employees banging the pottery with a steel stick to check if there were any tiny hidden cracks. “The pottery should sound like a bell” if there are no cracks, Garcia said. The fire-worked clay is then dipped for about three seconds in a lead-free yellow-like glaze which turns to white once dry, and “any tiny imperfections are reglazed,” Garcia said. “The fingerprint made while lifting the item out of the glaze is also filed down,” she added.

The individual creative paintwork which is done on each piece by the factory’s fifteen painters comes next. The designs are transferred to the ceramic by the use of carbon paper on a paper stencil, and the resulting dot pattern is then used as a guide for the handpainted designs. The length of time it takes to finish painting a ceramic piece depends on how intricate the design is and the size of each piece, the guide explained. When we visited, artists were painting huge urns, small serving dishes and 18 tiles that comprised the picture of the Virgin Mary.

When dry, the paint’s mineral colors change composition. Orange changes to yellow, black to green, brown to red, and light blue becomes dark blue, Garcia said. The earthenware objects are once again oven-fired, resulting in a hard, brightly colored surface. The pieces are now ready to be sold, either in the factory’s on-site shop or abroad, including the United States, Canada, Spain, Venezuela, and Peru. About 70 pieces a day are made by the approximately 200 employees, a sign of just how labor intensive the creative process is.

Jose Luis Hernandez from the local tourist office scraped the surface of a tile to demonstrate the high quality workmanship. The tile showed no signs of damage, a proof of its high quality, said the official who’d accompanied the writing group to the factory. “Although the prices are high, the pottery is genuine” and not all local shops are selling the real thing, he emphasized.

Besides a visit to the pottery factory, the city’s compact, historic downtown is famous for the many 17th and 18th century colonial buildings that are ornately decorated with Talavera tiles. With more than seventy churches and one thousand colonial buildings in the central area alone, visitors feel like they are walking around an open air museum.

An outstanding use of 16th century Talavera tile is found in the former kitchen in the Ex-Convento de Santa Rosa de Lima. The building is now the state artisan museum, or Museo de Artesanias del Estado. The kitchen’s huge, multi-domed interior is covered from top to bottom with the famous tilework. However, what may be even more interesting for the locals is what’s said to have been invented there – Puebla’s renowned mole sauce. The dark colored sauce, which can contain up to one hundred ingredients, is supposed to have been invented by the Dominican nuns as a surprise for their demanding gourmet bishop. Mole sauces, which have many different flavors, generally contain fresh and smoked chile, pepper, peanuts, almonds, tomato, onion, spices, and, of course, chocolate, of which the best known is made with a bitter variety. Food supplies in the kitchen were cleverly kept cool by a double wall that had water running in between.

The Museum of Santa Monica is another worthwhile stop. Generations of nuns secretly hid there when the Reform Laws of 1857 closed church-owned buildings after Benito Juarez separated church and state. To survive, the nuns sold candies and embroideries during almost eight decades of clandestine activity.

The museum houses religious art and items of self-flagellation, including whips and crowns of thorns in some of the former nuns’ penance rooms.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception is considered one of Mexico’s best proportioned cathedrals, is the second largest in the country, and also has the highest towers. Built between 1575 and 1649, the main altar has sixteen marble columns, and the large floor and several statues are also made of the same material. Gold leaf decoration is used in some of the many chapels, and a huge bronze statue of the Virgin Mary weighs 300 tons. When I visited, a priest was hearing a penitent’s confession without the usual private door separating them.

The Amparo Museum has an excellent collection of pre-Hispanic and colonial artifacts displayed in two linked colonial buildings whose architecture was influenced by indigenous designs. A glass case displayed an unidentified animal and perhaps a man about to be sacrificed in Veracruz some 2,500 years ago, and there were also Olmec masks, a feature of Olmec civilization three millennia ago. The museum, which opened in 1991, was the first in the world to have a computerized touch screen that answers visitors’ questions about museum artifacts.

The House of the Puppets, near the main square, is the city’s most comical structure. The building’s exaggerated statues are a caricature of the city fathers who took the house’s owner, Agustin de Ovando y Villavicencio, to court because his building was taller than theirs. He added the statues, which represented various officials, to get his revenge on the small-minded officials.

The Barrio del Artista, on the pedestrian-only Calle 8 Norte, is a lovely place to wander around while looking at artists at work in their open studios. Their paintings can also be purchased. The imposing principal theater, or Teatro Principal, is nearby.

Other unusual but-worth-visiting-places, which I didn’t have time to see, include the African Safari Park, reputed to be one of the best places in Mexico for African wildlife. The park is located about ten miles southeast of the city. I also didn’t have time to visit the house of culture, or Casa de la Cultura, a classic brick and tile Puebla building that occupies a block facing the cathedral. Formerly the bishop’s palace, it is now home to the tourist and other government offices. The Palafox Library upstairs has thousands of valuable books, including the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle which has more the 2,000 engravings.

Puebla is noted for its cuisine, and many consider it to be the best in the country. It’s believed that the Santa Monica nuns (cooking rivals to the mole-making Dominican nuns) invented chiles en nogada, a seasonal dish that’s available from July to September. It’s said to have been created in 1821 to honor Agustin de Iturbide, the first ruler after Mexico’s independence. To make chiles en nogada, a poblano chilli is filled with ground meats and fruits. It is then covered with a sauce of chopped walnuts and cream, and topped with red pomegranate seeds. The overall effect is colors representing the green, white and red of the Mexican flag.

For deserts, Sweets Street, as its name implies, sells almost nothing but things-bad-for-the-teeth – candies, including camote, a popular regional treat made from sweet potatoes and fruit, and cochinitos, which is made of bread, molasses and sugar. Famous treats from other regions like crystallized fruits, coconut candies, and bisnaga, a sweet made from cactus and sugar boiled together, are also available in the many sweet-tasting stores.

Sweets Street was a fitting ending to a city well worth a return visit.

This article is from the August 2001 – September 2001 The Mexico File newsletter. Back Issues and Subscriptions available.

Yvonne Moran is a freelance writer and a former general assignment daily reporter. Her stories have been published in The New York Times, Connecticut Post, The Advocate, Greenwich Time, Irish America Magazine and Fairfield County magazines, amongst others. She contributes travel stories to several websites and also writes for national Irish newspapers and magazines. She has been writing about travel for more than a decade. Yvonne contributed an article on Chiapas for the July 2001 issue of Mexico File. Yvonne can be reached through email at ymmoran@aol.com for comments and questions. For this article, she visited one of the Puebla’s most famous pottery factories, but discovered that the city offers a lot more besides.