The production of glazed earthenware pottery was one of the earliest and most developed industries of New Spain, as colonial Mexico was called. The principal center of production, Puebla de Los Angeles, located south of Mexico City, was making wares by 1573. By the mid-seventeenth century, the Spanish had established a number of workshops in Puebla, and a potters’ guild was formed to control quality.

The production of glazed earthenware pottery was one of the earliest and most developed industries of New Spain, as colonial Mexico was called. The principal center of production, Puebla de Los Angeles, located south of Mexico City, was making wares by 1573. By the mid-seventeenth century, the Spanish had established a number of workshops in Puebla, and a potters’ guild was formed to control quality.

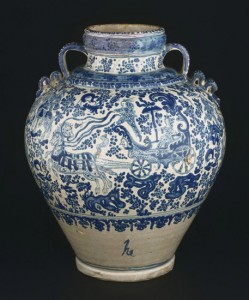

The pottery from Puebla was called Talavera de Puebla because the wares were intended to rival the Spanish pottery from Talavera de la Reina, a city near Toledo, Spain. Although the Mexican Indians had a thriving pottery industry at the time the Spanish arrived, the Europeans produced wares using their own techniques of wheel-thrown ceramics and tin glazing. The pottery from Puebla belongs to the majolica type, having an earthenware body that is covered with a white lead glaze that is then painted with colored glazes. Established in Europe by Islamic craftsmen in Spain, this technique is the same for Italian majolica, French faience, and Dutch delftware.Colonial Mexican ceramics are distinguished from the Spanish by the original ways in which Mexican potters absorbed artistic traditions from the East and West. European ceramics were imported to Mexico beginning in the late sixteenth century, and Chinese wares were plentiful since Mexico was on the Spanish trade route with China.

The impact of Chinese blue-and-white ceramics can be seen in the number of pieces from Puebla with a cobalt blue glaze. And the forms of the drug jar and vases were inspired by Chinese vessels. Other influences came from the Spanish colonial experience. Two tiles depict Native American warriors with feathered skirt and cape. An interesting substitution can be seen on the vase with iron hardware, where a stylized Mexican quetzal appears instead of a Chinese phoenix. The tiles with religious subjects remind us that tiles were made by the thousands to decorate Mexican churches, monasteries, and graveyards.The freedom Mexican artists exercised is seen best, perhaps, in the large vase that juxtaposes a European woman in a chariot with a host of animated Chinese figures. The humans and animals are filled with dots, an Islamic tradition for indicating living figures. This surprising, vibrant creation unites several worlds of art in one object.

Philadelphia Museum of Art – Summer 1992