The culture of Mexico reflects the country’s complex history and is the result of the gradual blending of native culture (particularly Mesoamerican) with Spanish culture and other immigrant cultures.

The culture of Mexico reflects the country’s complex history and is the result of the gradual blending of native culture (particularly Mesoamerican) with Spanish culture and other immigrant cultures.

First inhabited more than 10,000 years ago, the cultures that developed in Mexico became one of the cradles of civilization. During the 300 year rule by the Spanish, Mexico became a crossroad for the people and cultures of Europe, Africa and Asia. The government of independent Mexico actively promoted shared cultural traits in order to create a national identity.

The culture of an individual Mexican is influenced by their familial ties, gender, religion, location and social class, among other factors. In many ways, contemporary life in the cities of Mexico has become similar to that in neighboring United States and Europe, with provincial people conserving traditions more so than the city dwellers.

Mexico is known for its folk art traditions, mostly derived from the indigenous and Spanish crafts. Pre-Columbian art thrived over a wide timescale, from 1800 BC to AD 1500. Certain artistic characteristics were repeated throughout the region, namely a preference for angular, linear patterns, and three-dimensional ceramics.

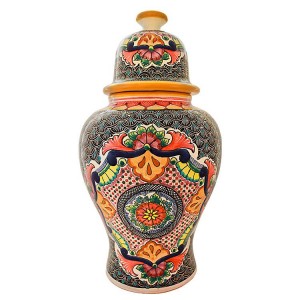

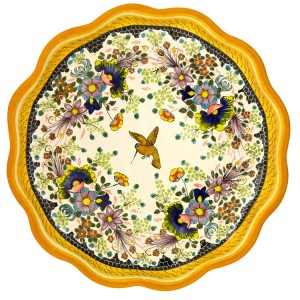

Notable handicrafts include the Talavera of Puebla, the majolica of Guanajuato, the various wares of the Guadalajara area, and barro negro of Oaxaca.

In the early 20th century, interest developed in collecting Talavera Pottery. In 1904, an American by the name of Emily Johnston de Forrest discovered Talavera on a trip to Mexico. She became interested in collecting the works, so she consulted scholars, local collectors and dealers. Eventually, her collection became the base of what is currently exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Her enthusiasm was passed onto Edwin Atlee Barber, the curator of the Pennsylvania Museum of Art. He, too, spent time in Mexico and introduced Talavera into the Pennsylvania museum’s collection. He studied the major stylistic periods and how to distinguish the best examples, publishing a guide in 1908 which is still considered authoritative.

During this time period, important museum collections were being assembled in Mexico as well. One of the earliest and most important was the collection of Francisco Perez Salazer in Mexico City. More recently, the Museo de la Talavera (Talavera Museum) has been established in the city of Puebla, with an initial collection of 400 pieces. The museum is dedicated to recounting the origins, history, expansions and variations in the craft. Pieces include some of the simplest and most complex, as well as those representing different eras.